- Home

- Lisa Mannetti

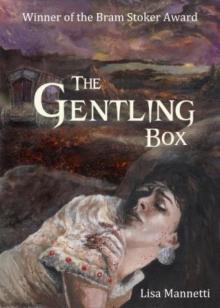

The Gentling Box Page 3

The Gentling Box Read online

Page 3

“I—” I didn’t know what to say. There was something deeply persuasive in his voice, and the idea held a kind of pearly glow, like the deep comfort of a pleasant dream. Yes, I could pretend I lost the way, we would see the grave in the woods, Mimi would stand, head bowed, brushing tears from her eyes, and then we would pack our things, take Lenore, and leave the country forever. And then a small nagging voice spiked through me: She’ll know, she’ll guess and she’ll never forgive you.

“I can’t do it,” I said. “Anyeta was her mother. She wanted to come, she deserves to see the old woman one last time before she goes into the ground.”

“Suit yourself.” He shrugged and began to stiffly climb down from the wagon.

“Look, Mimi’s told me the others were terrified of her mother, but you know the Romanians, Joseph—Christ, if you believe them every town has more ghosts than people—and the gypsies are even—” I stopped, ashamed of my slip.

“Worse,” he finished. “But seeing more, they have more reason, perhaps.” He touched one finger alongside his bony eyesocket. “You’re like your mother, Imre. You never believed—not even when your senses might have told you different.” He paused, one hand played over the lead horse’s nose, the horse nuzzled his palm. “Keep your skepticism, half-gypsy, as long as you can—but don’t let Mimi go into the old woman’s wagon alone.”

“Anyeta’s dead—”

“I know,” he said, slapping the horse’s flank lightly, “but if they catch her alone with the body, there’s going to be a lot of ugliness.”

Joseph limped toward his barrel-topped caravan. He paused, coughing painfully, then heaved himself up onto the box. He’s grown old, I thought sadly, clucking to gee up my team, and the old are more liable to superstition. Then his wagon, perpendicular to mine, shot ahead in the early gray light, and for a second I would’ve sworn the reins were gathered in a knot to one side of the rail, and that he was resting, arms folded, a cigarette idling between his pale thin lips. But that was impossible. No unguided team could navigate the pitted twisting roads in this godforsaken country. I was tired, it was foggy, it was a trick of the light.

-5-

An hour and half later we drove into the camp. I pulled into the rough semicircle of ten or twelve shabby caravans ringing a communal fire. It was just a little past dawn and I was surprised at the emptiness of the place. A baby wailed from inside one of the wagons, making the tree lined clearing with its dark towering pines seem lonelier still. I was just about to ask Joseph where the other gypsies—what he would call the Vaclav-eshti—were, when I turned to see him disappearing through the canvas flaps of a faded blue wagon. Sighing, I unhitched my horses, set them to crop grass, then walked toward the rear of the caravan to go in and wake Mimi, tell her the news.

Behind me I heard a swift rattle of chains. Someone’s monkey—before I could complete the thought, a short tubby man, dark hair twisted into greasy spikes, leaped out at me, forcing me against the caravan. I heard the slither of the chains at his feet, saw the broken end of one link.

“Wa—re, wa—re,” he gibbered in a broken guttural voice. He went on tiptoe, pushed his stubbly face into mine, and I smelled the hot sour odor of decaying teeth. He began to mutter again and I turned my face aside, but not before I’d seen the raw wound where his tongue had been cut away.

I tried to dodge him, moving from one side to the other, but he was quick. His hands shot out, thwarting first one of my shoulders, then the other. I bounced between them like a steel ball rattling back and forth against the pins in a game of bagatelle, while he laughed at me.

“Constantin,” Joseph called out sharply. I saw the old man standing at the end of the alley-like passage between the wagons. “Leave Imre alone.” The short man backed away at once and stood rubbing his wrists as if he were ashamed. I saw the red marks of handcuffs on his skin.

Joseph grabbed Constantin’s arm and attached one end of a pair of old heavy manacles. “Where is it?” Joseph demanded.

The tubby little man made a gurgling sound, shrugging off the question. “None of your nonsense, hand it over,” Joseph said. The man hung his head—like a child with a jelly smeared chin caught reaching for a second bun.

“C’mon,” Joseph said, putting his hand out. Constantin squirmed his bottom, then reached inside his trousers and withdrew a file. Joseph took it from him and put it in his own breast pocket, saying, “I keep him in my wagon most days—not last night, though. I went in to fetch him from Stephan, who was out cold. Hangover,” Joseph grunted. “Constantin saw his chance and cut the chains and cuffs. I knew he’d be here.”

“How?” I lit a cigarette to calm my nerves.

“Constantin sniffs out anything out of the ordinary—like the arrival of another caravan.” Joseph paused, and he tugged at the gold ring on his middle finger.

Constantin. I knitted my brow. I knew the name. The memory of a plump young man rose in my head. He’d been a great practical joker, a good storyteller. “He went mad?” I breathed.

Old Joseph nodded. “Anyeta did it.”

“Say what you want about her, but you keep him in chains.”

“He wouldn’t hurt anybody, that’s so he doesn’t hurt himself—again.”

A spurt of revulsion sluiced through me. “He—Constantin cut out his own tongue?” As soon as I said these words, the short man screwed up his eyes and began to weep, his mouth jerked and twitched. The dark stubble on his face shone with a mixture of tears and saliva.

“That’ll do,” Joseph said, then turned to me. “If he gets to crying hard, he’ll start howling. It’s hell on the nerves.” Joseph laid one hand on Constantin’s head, and I had the uneasy feeling I was watching a dog heel to his master. “Buck up, now,” Joseph said. Sniffling, Constantin wiped his face with his sleeve and smiled weakly.

I couldn’t look at him. The ghostly little grin was more horrible than his tears.

“Two—maybe three months ago,” Joseph said, “we heard a big ruckus in his wagon. Shouting. He was screaming, over and over, ‘I’ll teach that liar’s mouth to smart off to me!’ and then we heard shrieks, a series of thick babbling grunts, the sound of hammering.”

Joseph’s lips were tight. “We had to break the door. When we got inside, he was passed out at the table, lying with his face in a pool of blood. He didn’t just cut it out—the severed tongue was smashed against the table,” he said. “And if you ask me what was worse—the sight of his white face with the blood pouring over his lips, or the sight of the pulverized flesh clinging in flecks and gobbets to the head of the hammer—I’ll tell you I don’t know.” He closed his eyes. “I see them both—his face and the bloody hammer—in my dreams.” He paused. “So I keep him with me, keep him clean and comfortable—as much as one man can do for another.”

“And you believe Anyeta cursed him?”

“Imre,” he said tiredly, “there is much I’ve seen—more than there’s time to tell you. Let your wife do her duty, and take your family away.”

He led Constantin off, and I considered what he’d said. The last advice was sound, certainly. I crushed out the cigarette and looked up. In the distance I could see Anyeta’s peeling yellow caravan, driven out of the rough circle in the clearing. The whole campsite had a dispirited, depressing air—here and there I saw a rusted chimney flue slanted at a weird angle over roof boards, or a set of stairs made from knocked-together crates—as if times were hard of late, and I thought about how poverty and superstition went hand in hand. Young men dream of the future, of prosperity; it was the poverty that chafed and galled me twenty years ago—and standing there, I suddenly remembered exactly why Mimi and I had left the troupe:

“What’s that in the bag?” Mimi had asked. She was too thin in my opinion, recovering much too slowly from Elena’s stillbirth. It was dusk and I’d just come into the caravan carrying a large burlap sack, and the smell in the air told me we were about to sit down, for the third night in a row, to another supper of roasted

onions.

The troupe was camped in the mountains near Tirgu Mures I recalled, and all that winter there’d been no money in the district, and therefore no horse trading. All of us were pinched and pale—except Anyeta—she looked as rosy as a milkmaid lapping cream night and day. Now it was coming on for spring, but I’d spent another depressing day in town to scare up a few lei, and I’d fallen back on what were time-honored occupations among gypsies, but for me strictly marginal work. I’d spent a dull morning shining shoes and grinding knives. In the afternoon I had the choice of two other menial jobs commonly given to gypsies—teeth pulling or rat catching. The idea of chasing around someone’s mouth for a rotted tooth seemed even more horrible than grubbing behind dank walls for the rats. And after I consumed a very small loaf of bread and dispensed a very large hunk of palaver, I struck a deal and shook hands over a dirty wooden counter with the fat owner of a cheese shop.

Inside the dank cellar under the shop I found myself wishing I were in a field, listening to the ringing sound of the anvil, the whinnying of horses instead of the squeak and scrabble of rats. With a sigh, I brought out what I privately called the tools of the rat pulverizing trade—a hammer to clobber them and a bag to stuff their bodies inside.

But the rats were cunning at hiding from me, and I’d been so late at it the cheese shop owner finally left, taking his cash box with him and leaving his underling to put up the shutters and lock the door. The shop keeper promised to pay me 50 lei per rat when he returned in the morning. I didn’t trust the underling—a pimple faced boy of thirteen or fourteen—to keep track of my quarry. In fact, he looked like the kind of boy who could think of several interesting things one could do with dead rats, from scaring small children to seeing how rodent guts splattered when you lay the filthy creatures in the road and watched horse carts run over them. So instead of leaving the dead vermin in the shop cellar, I brought my bounty—four or five large ugly gray brutes—home.

“Is it meat?” Mimi said. I guess my frustration made me decide the countermeasure of a joke was in order.

“Yes,” I said, plumping the burlap bag onto the table.

“What kind?” she said, untying the knotted rope that held it closed.

“Mostly dark,” I said, at the same time she peered deep into the sack and began to shriek.

“Rats!” she shouted. “Oh mother of God, you can’t mean you expect us to eat these disgusting rats!”

“I admit they’re a little scrawny—but somebody else beat me to the choicer, plumper specimens in the butcher shop—”

She suddenly pressed her hands to her eyes; at first I thought she was laughing; a little hysterically, perhaps, but then her shoulders shook and she began to sob. I took her in my arms. She tried to shrug me off but I held on, saying over and over I was sorry, cursing my stupidity. It had been a mean winter for everyone, and spring had finally come but nothing was better. The thought crossed my mind that she was crying not on account of the rats but because she was secretly afraid she’d lost the baby because of the scant food.

“We have to leave, there’s nothing for me here,” I said.

“I hate the wandering, the endless roaming,” she said, and I nodded, knowing she was feeling edgy and weak and I debated whether or not I should tell her about two incidents.

Yesterday I’d seen a man burning down his own house, the flames roaring against the gray sky when the small bright tiled roof collapsed. It was five years before the revolution of ’48, when Transylvania would be ruled by the Habsburgs, but like all uprisings, the seeds were already being sown. He had no money to pay the chimney tax; they would take his land if he didn’t pay. “Now I got no chimney, Mister, and I don’t owe no tax,” he’d said, pointing to the black tumble of stones and spitting on the soft brown mud between his cracked boots. “But where will you go?” I’d asked. His round, chapped face was impassive, his voice dull with resignation. “Up there,” he said with a sweep of his arm, toward the towering mountains on the horizon, “to the hills.” I wasn’t sure what he meant, I guessed he saw the puzzlement on my face, my brows narrowing, and he went on. “To the caves, Mister. I will take my wife and my children to live in a cave.” He shivered lightly in the cool spring breeze. “God takes care of the animals, perhaps things will go better next year, or by His grace, the year after that.” In my mind’s eye I pictured the farmer and his family huddled inside a cold stony tomb like a dark wet mouth and I shuddered. The fact that Mimi and I were living in a caravan was meager comfort. I felt my heart pound lightly with anxiety; I wondered if things would be better next year or the year after that, if telling Mimi about the other incident would frighten her, or maybe make her angry enough to leave—

“We could ask my mother for money,” she said, taking my hand lightly; unconsciously she had keyed into my mental debate, and I winced. A month or two before I’d gone to Anyeta to ask for money.

“I don’t think so,” I said to Mimi, hearing Anyeta’s answer, her taunting voice echoing in my head: “Let your wife go whoring,” Anyeta had said, her eyes dancing as brightly as the flames behind the isinglass in her stove. She was warming her plump backside by the fire, her hands behind her, fingers stretched toward the glowing flames.

I stood there, feeling her eyes crawl over me and absently turned my black hat in small circles in my hands. I knew she had gold pieces by the dozen sewn inside her mattress.

Filthy bitch, I thought, dropping my eyes, telling myself to try another tack. “Mimi is your daughter.”

“Money is money,” she shrugged. She didn’t add whoring was good enough for her; instead, she moved off from the fire, flat hips swaying like a cat’s, and let her sensuous walk say it for her.

“She’s pregnant,” I said, seeing Anyeta turn her back and retreat to the other end of her cozy caravan. “I’m asking for her sake, because there are things she needs.” Ask her for a goddamn loan instead of a gift and get out, a part of me considered.

Anyeta sat on the edge of her bed and I heard the brief shift and tinkle of coins inside the feather mattress. At the sound, her sharp eyes fastened on mine. “I never loan money,” she said. She suddenly lay down on her side, one hand supporting her head with its mass of dark heavy hair, the other lightly sweeping back and forth, tracing a path between the place where her right breast touched the patchwork quilt and one hip rested.

“Loaning money is out of the question,” she said again, patting the red and blue quilt, and turning liquid eyes up to mine. “But I might give it—as a favor.”

I was a poor excuse for a husband, I told myself, but Mimi deserved better than this degradation—a life of poverty or a life of whoredom.

“And I’m no whore, either,” I said, turning to leave. I heard Anyeta’s throaty laugh when I shut the door.

Looking at the bag of rats on the table, I decided not to tell her any of it. I would make my appeal based on hope, on the future. I shook my head, “I don’t want to ask your mother. I want us to make a life for ourselves.” I told her my heart was in Hungary with the wild horses, and in my mind’s eye I saw the cowboys we called csikos wearing their wide sleeved linen shirts and hairy sheepskin capes, squatting by their campfires, galloping over the prairies.

I don’t remember everything I said that night, but Mimi took a chance on me. I never forgot that. She believed in me, agreed to risk the known for the unknown, and less than a week later we left Romania for good.

Now, standing in the tall grass and gazing at Anyeta’s broken-down wagon in the distance, I saw her malicious grin, heard her mocking voice in my mind, her contemptuous answer when I spoke of our need: Let your wife go whoring. It was twenty years later, the country was still ruined by poverty and superstition. We would take Old Joseph’s advice and leave soon, I thought; Mimi had trusted in me before, she would trust in me again.

I climbed the set of spruce little folding stairs I kept for when we traveled and went inside to tell my wife her mother was dead.

-6-

Mimi’s hand was clenched tightly in mine as we walked through the high grass toward Anyeta’s wagon. She’d taken the news better than I thought. She sat with her hands clasped between her knees, nodding vigorously as we all do when we hear something that shocks or stuns us. She didn’t say anything. After a few minutes she stood up from the table. Her eyes were misty looking, but she wasn’t crying hard.

Now I opened the canary colored door and Mimi followed me into the half gloom. Anyeta lay propped on her bed like a huge wizened doll. Her head lolled against her shoulder. Her dark eyes were open, staring vacantly and I saw that one of them had gone white and droopy looking. It bulged slightly toward her sharp cheekbone. Her scrawny hands were like wax sculptures hooked over the edge of the graying coverlet.

“Christ, they left her in filth,” Mimi said. She stepped to the foot of the bed, and nervously fingered one of the tatty muslin drapes that pooled over the warped floorboards.

“She must have been ill a long time,” I said, caught on the memory of her plump well-fed face as my eyes ranged over the room that had been once cozy, nearly sumptuous. Now, broken windowpanes were stuffed with balls of fabric. Bedding and ragged clothes were jumbled on the floor, trailing over the edge of the loft. A cupboard door hung crazily, disclosing shelves crammed with a grimy riot of pots and crocks and glassware. On the table I saw a clutch of sticky medicine bottles mingled with dishes of uneaten food, and the dusty remains of blackened herbs.

“The smell,” she said, wrinkling her nose.

I nodded. It was something like the gaminess of a wild animal den: a dreadful stench of dirt and feces and flyblown meat.

“It can’t be her—her body,” Mimi said, “not so soon.” Her eyes flicked from the pale wrinkled corpse to the gloomy disheveled room. She moved away and ran one finger over a water stain that swelled and bloated the wood of the right wall. “It makes my heart ache,” Mimi said softly.

The Gentling Box

The Gentling Box Deathwatch - Final

Deathwatch - Final