- Home

- Lisa Mannetti

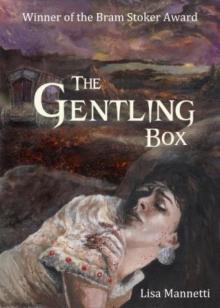

The Gentling Box Page 11

The Gentling Box Read online

Page 11

It was one of those rare days we are sometimes given, when each moment, every impression stands out—perfect, discrete: the leisurely drive along the peaceful, country roads, the sight of the oxen plodding in the sunshine; the old glass lanterns fastened to graceful iron arches and set directly into the buildings; the way the lamps glimmered at twilight in the steep streets; the sound of the bells ringing out the hours; the rhythm of young bodies that seek pleasure and find delight.

We both loved—and neither of us ever forgot—Sighisoara; and on our way home, we stopped the caravan on the side of the tree-lined road and made love in the moonlight. Mimi, my bride-to-be held me against her small chest, met my ardor with an urgency of her own.

I remembered fondly looking down at her body under mine, seeing her pale hand—silver in the moonlight—dart up to smooth my cheek. I saw her quick smile, heard her tease: “My own, my Vlad Tepes.”

It was Vlad Dracul’s other name; she’d called me Vlad the Impaler. Then she raised her head swiftly, her wet lips touched mine for the space of a heartbeat, and we both laughed.

***

“Yes, she told me about the first day, the first time—the private joke about Vlad the Impaler,” Zahara said, and I was too surprised to blush. I turned it over in my mind, thinking her cousin must have meant more to Mimi than I ever knew, if Mimi had confided this . . . .

“She came to me, right before the wedding,” Zahara went on, “she held my hands in both of hers. ‘I want you to know,’ Mimi told me, ‘of all the troupe I love you best, and I have something for you.’ It was her wedding, and she had a gift for me. It was a pendant.”

I closed my eyes, seeing that dusty shop in Sighisoara, the gleam of Mimi’s smile, the charm winking against the darker skin below her throat—

“Silver, the shape of the crescent moon,” Zahara said. Her hand crept toward her collar, and she loosened two tiny shell buttons. “You never knew she gave it to me,” Zahara said in a voice that was husky with emotion, “but I have it still.” She fingered the fine-linked chain at her throat, tugged slowly. And I saw the silver moon I’d given my beloved rise up from between her breasts.

Sighisoara, I mourned inwardly. A fairy tale.

It came into Zahara’s hand, we both stared at her palm, at the fragile ornament lying against her skin, and I heard her voice hitch. “It was Mimi’s and because she loved me, she gave it to me.”

I bent to touch my lips to the silver shape in her hand, and as I inclined toward her, I had a sudden glimpse of the flesh below the frilled cuff of her blouse. I felt the ache of despair, and a moan escaped me. Zahara’s wrist was white and smooth—as white and unmarked as Mimi’s had been before this terrible evil assaulted us.

I stopped, gazing up at her. Her onyx eyes met mine, and I saw a questioning light there. “Oh, Zahara,” I whispered, “Mimi said you claimed the hand of the dead.”

“Joseph—” she began.

“Joseph made her think so,” I finished sadly. I closed my eyes, my head fell forward, and her arms were around me, comforting me. Her voice was soothing, a murmur. She was saying Mimi’s name over and over. The sound of my wife’s name was like the distant roll of waves breaking on the shore; I felt as lonely as a man who is cast adrift to drown in the nightsea and who yearns for light, wants to touch land, hears the haunting peal of the ship bells fade, then finally cease.

“Mimi,” she breathed again.

We held each other. My hands found her hair, turned her face up to mine, and weeping for Mimi, I kissed the salt from her skin.

-22-

We made love. And, that grief-filled first time, it was for Mimi—as if we both made love to my wife. But the second time at dawn was ours, for the years of buried passion that had risen again between us.

I woke gradually. The room seemed to hang suspended in the time between night and day; lurid streaks of light vied with deep pockets of shadow. The sun picked out scatterings of clothes—trousers, a filmy chemise, a white, work-worn shirt, cotton stockings. Zahara leaned over me, and I felt her lips nuzzling the tender flesh just under my ear.

Her hand played over my chest, fingers idling in the graying twists of short wiry hair, and I closed my hand over hers. I turned to meet her gaze and felt her full lips press to mine. She smiled behind the kiss as if she had some sweet secret, and the gesture was so girlish, innocent and womanly all at once that it inflamed me. Slow, I reminded myself, and let my eyes fall shut.

I caressed the nape of her neck, let my hands sift through her thick shining hair. It was cool, gossamer soft against my fingers.

“Imre, my love,” she sighed into my mouth, and her breath was warm and comforting, her tongue luscious against mine. I felt her shift, straddling me lightly, and I opened my eyes to look up at her. Zahara’s head was canted back, her face serene with a half smile. Her skin was a dusky olive. I brought my hands to her breasts, rounding them slowly, gently scissoring the dark brown nipples between my first and second fingers. Far away, I could hear her uttering a kind of deep, sweet humming.

She leaned forward. I tasted her breasts, felt their round weight against my lips, my chin. I slipped one hand between her legs, the flesh of her thighs gave off a warm soothing radiant heat. She was slick. Wet.

I felt her turn, take me in her mouth, her hands moved over me slowly, at the same time I slipped my fingers inside her, skirled them around and around the small hot button of flesh. I heard her breath coming harder, the sound of her light sighing moans, and I felt myself shudder, nearly come to climax. I was aware of the wetness her mouth left on me when she pulled away to straddle my loins.

I felt her fingers guiding me, and then I was inside her, helping her lift her hips that we might lift and fall more delightfully. She shifted her weight, we clung to one another, took a slow spin, and I was on top, feeling the whole wondrous depth of her. I looked down. Her eyes were closed, her lips redder with our kisses, her dark hair was a rippling fan against the sheets. I felt her teeth, the slight pull as she nipped, drank up the skin of my throat. Her legs opened and closed around my back, I bent my lips to one nipple, and the image of myself at seventeen kissing her breasts beside the nightskin of a gnarled tree rose unbidden in my mind, and I felt the beginning of that letting go that brings you to the end.

***

Afterwards I lay on her chest a long while. Her hands moved slowly through my hair, across my shoulders, up and down the tender skin of my back.

“I’m in love with you,” Zahara whispered, tugging lightly on a small tuft of my hair, and making me look into her dark obsidian eyes.

I stared into them a long time. I smiled, but I made no answer.

***

She was lying on her back sleeping when I woke some hours later. I never eat breakfast, my stomach is a much later riser than the rest of me, and the very idea of food in the morning registers as a faint queasiness inside me. But I was hungry that day, and the flashing image of scrambled eggs, fried potatoes, sizzling chunks of meat, brown coffee set my stomach growling and brought a grin out on my face. She was sleeping heavily. I would fix the food, I thought, popping out from under the covers and hustling into my clothes.

I was bent over and had one leg stuffed into my pants when I heard a thick gobbling sound, followed by the riffling of a protracted snore. It startled me briefly, and I chalked it mentally to save as a tease. Just about everybody snores sometimes, but we keep it private, a secret—along with the rest of our noisy body signals. Smiling, I pulled my trousers up and glanced across the room.

The window by the side of my bed admitted light, but the sun had gone round to the other side of the caravan, making the room duller than it might have been. Zahara’s skin had an unfamiliar pasty look, thicker somehow than I remembered it, with a greasy whitish cast like lard. The sheet made a rumpled dividing line over her belly. One arm was thrown back over her head.

I moved closer and the room was suddenly much darker, dim with shadows as if the unseen sun had

gone behind a patch of heavy clouds. Under the sheet, her legs and hips appeared to have taken on a bloated swell. Her belly and midriff were wide, round, pocked with dimpled flesh, marbled with tiny capillaries that gave it the faintly pink look of butcher’s pork. Her breasts hung slablike, pulled out of shape by their ponderous weight. I saw a deep fold of slack skin at the point of her shoulder where her arm was raised over her head. The elbow was pudgy, wrinkled. I sucked in my breath. But that only happens when a person is enormous—Christ, you can waddle around for years before the fat begins to deposit at your shoulders, your elbows—

—The rest of us see an overblown, sloppy woman who waddles when she walks—

Joseph’s words jumped in my head. I felt a slow churning in my belly. No, he planted the idea in your brain, and it slowly ripened with time into black fruit—

I stepped nearer the bed. Her mouth was open, her chest rose and fell sluggishly, her breath came out in short heavy puffs. In the gloomy light, her hair was mousy, shot with gray, her teeth took on a sickly brownish tinge—

—Three of her teeth are missing—

For a second I saw the dark gap, the shrunken stunted pink of her gums where the teeth had fallen away, her tongue turned and clicked in her mouth, her lips came together with a tiny flapping sound. I leaned closer, breathing in a foul cloud. Gagged on a stench that rose from sordes, the crusts that jacketed her rotting teeth and gums, from the accumulated gases deep within her.

I drew back, turned away and clapped my hand over my nose and mouth. Impossible, I told myself. It was guilt making a slow subterranean course through my brain, finding its way to the surface in the memory of the old man’s hideous words.

—What do you see, Imre? The rest of us see—

The right side of the mattress sagged beneath her humped body, listing under a vast weight. I moaned inwardly. A man would roll to the center of that, fetch up against the meat of her. I felt my mouth twitch. A mental image of my hand playing between great jiggling thighs, of kissing a broken sour mouth creased with wrinkles rose up. In my mind’s eye I saw Constantin’s picture of the fat, chinless woman, her splintered grin in profile. The snaky writing spun up at me. Witch. I shuddered, telling myself Constantin’s a madman, and closed my lids.

I rubbed my hand against my brow, forced myself to look again, then breathed a sigh of relief. I saw her full reddish lips turn up, Zahara smiled in her sleep and settled on her side—her slim body undulated in a long slow curve—like any love-sated young woman.

I shoved my disquiet aside and left the room, walked up the short flight of stairs to the kitchen. Moving softly I took out the tin pot, then set coffee on to boil. I stood by the window, absently looking out while I waited for the coffee. In the glass I caught sight of a tattoo of bluish-purple marks—love-bites—dotting my throat. I lowered my eyes from the reflection, began buttoning up the collar of my shirt, and as I brought my hand up I smelled the dank odor of her sex on my fingers. I felt a spurt of fear rising up inside me; I went to the basin and began to wash, an old Kalderash gypsy saying swirled inside my head. Kon khal but, kal peski bakht. He who eats much, eats away his luck.

I was only dimly aware that my appetite had left me.

-23-

Late Autumn, 1863

Day after day I drove the caravan through country lanes and mountain passes, always searching for some sign of Mimi, of Lenore. We asked in towns; spoke to grim-faced farmers nodding tersely as they leaned over broken fences, shook my hand, wished me well. We stopped at the fairs and marketplaces. Always the same result. No one had seen her, seen a young girl, seen an old gypsy man pass through driving a beaten wagon.

Zahara never said a word to me about this long fruitless search; I never mentioned that I had the feeling Mimi was trying to find her way to me.

It was getting close to November. We’d camped near Deva. In the distance, the mossy ruins of the old Citadel loomed above the hills. Zahara was in the caravan; toward sunset I unhitched the team and led the horses to a meadow to let them graze. I watched them crop a while, their mouths working at nibbling the hay stubble; then I saw that a chestnut mare was favoring her right foreleg.

“Stone, for sure,” I said, advancing, and taking a pick out of my pocket. As I stooped to examine the hoof, I heard my name drifting over the silent yellow fields.

Imre, Imre.

I looked up, oddly certain it was her, that Mimi called to me. But there was only a covey of quail taking sudden flight. As if they’d been routed, they rose in a flapping cloud, vented their shrill cries, and I felt a mad skittering in my heart. I looked out over the meadow.

There was an ancient stunted tree in the center that made a rude shelter for cattle during summers. The wind blew up, and I heard the bare limbs rattle against each other with a skeletal sound like the bones of dead men. The top of the oak blazed with fierce red light, the bottom lay in thick twilight mist. The sun dipped over the horizon all at once, and I felt a keen excitement all along my spine, as if some moment that was out of time was bearing down on me.

And then I saw it. The old man’s barrel-topped caravan was there; a wavering image rising out of the gray mist beneath the tree. I held my breath.

The skin of the canvas seemed to disappear, and then I was seeing inside. Pale ochre light from a rusted lantern spilled in a circle over the table. Mimi got up, filled a white soup plate with stew from an iron pot on the small black stove. She carried it back, set it in front of the old man. Lenore smiled, held up her dish for a second helping.

I took one long step nearer, the caravan seemed to fade into the swirling fog, and a groan was wrenched out of me. I stepped back, the vision returned and I was suddenly aware that I was hearing them—

“He will come to it in time, my dear,” Joseph said, patting Mimi’s wrist, and I saw the gleam of his gold ring on his thin finger, the sly look in his hooded eyes. Did the old man think I would claim the hideous power, too?

“It’s so long, so wearying,” Mimi sighed. “This endless waiting,” and I saw her glance at Lenore, as if there was something my wife was torn between telling our daughter and keeping from her, too. Mimi’s face was too thin, she looked weary, pain burdened. She told Lenore to finish her supper and get ready for bed. My daughter—her hair hanging in thick brown braids—stood before Joseph. I saw the old man kiss her brow, and I felt a sickly dread in my heart. He’s bewitched them, set his mark on their minds, gives them kisses worthy of Judas.

Mimi moved toward the doorway, crossed her arms at her waist, and I saw her gaze out over the darkening field and I wondered if her eyes found mine, if she saw me. A moan came out of my throat and I began running toward her. With each step the caravan dimmed, until at last there was only the single silhouette of Mimi’s form—the froth of dark curls around her head, the bell shape of her long skirt—the fading sound of her voice, a sigh, and then a whisper—

Imre, Imre

—that became silence.

There was nothing under the oak. I searched the ground, tramped in circles around and around the trunk. My eyes bulged, my head ached with the strain of trying to see in deepening shadows, of looking for trampled grass, a forgotten handkerchief, a scrap of food—for a sign, for just one more glimmer, the merest touch.

Were they here now? I wondered, striking the tree with my fist. Had they been here before, or were they coming some night in the future? I didn’t know, I was reluctant to leave. For me that autumn-clad field was a romantic, haunted place; the nearest I’d come to finding Mimi and Lenore. And I think I might’ve spent all the sunsets of my life in the meadow waiting for them; but in some deep part of me I knew no vision would come there again. There was no denying the sudden emptiness of the place, the sense that its magic was fled, and after three more lonely evenings, I gave it up, feeling sad and heartsore.

***

If my days belonged to Mimi, I will tell you frankly that I was a divided man—and that division was just as sharp as the line between ligh

t and shadow in the tropics—so with the growing darkness of the season, my nights belonged more and more to Zahara.

We made love with an abandon I had never known, but out of that wildness a sickly thing grew between us. Like a fat leech, it fastened and fed on our sweat and groans and cries.

It began innocently enough, like the larking adventures two daredevil children might share. We’d been teasing each other—and getting steamed up—all through a long supper that we had sitting side by side on a bench. Zahara was wearing a white linen shirt of mine; and if the sight of her bare legs wasn’t enough, the thought that she was naked under the shirt was. Every time she leaned or shifted the shirt collar flapped wide and gave me a tantalizing peek at her breasts, at the smooth expanse of skin just below them.

“Oh, here I went to all this trouble and you’re not eating,” she said, giggling, shaking her head at my food laden plate, a sarmale of cabbage leaves stuffed with rice and meat.

“Cooking is not the trouble you went to,” I replied, pointing at her. “Dressing—or undressing, I should say, is what you concentrated on.” I leaned back against the wall of the caravan and nudged my dish toward the center of the table.

“Did it work?” Her eyes were bright with mischief. She suddenly faced me, her chest held high. “Did it?” she whispered, lightly nuzzling me with her breasts. “Yes, I wonder if my plan—” I felt her hands scrabbling in my lap, and I gave a small groan.

“Yes, you little witch, your scheme worked,” I said, at the same time I tore the buttons of the shirt away and bent my mouth to her breasts.

The Gentling Box

The Gentling Box Deathwatch - Final

Deathwatch - Final